Since posting about Glenn A. Baker's radio show, I've found these clips of Glenn playing three requests for me. This is probably in 1979, perhaps late 1978. At the end of the second clip, Glenn mentions upcoming guest Kim Fowley, the larger-than-life pop producer he often featured on the show.

Rock'n'roll Trivia Show clip #1 (1m 25s)

Rock'n'Roll Trivia Show clip #2 (2m 34s)

The quality is lo-fi: I was pulling in 2JJ some 500 km to the north, and taping onto an audiocassette which I've since grabbed onto mp3 without enhancement.

Music and sidetracks of the 50s, 60s and 70s, more or less related, or not, to my Australian song history site "WHERE DID THEY GET THAT SONG?" at POPARCHIVES.COM.AU

13 December 2006

▶︎ Audio clips from Glenn A. Baker's Rock'n'Roll Trivia Show, c.1979

11 December 2006

▶︎ Augie Rios - Ol' Fatso: an obscure Christmas novelty

Ol' Fatso is about an unbelieving boy who jeers at Santa, Don't care who you are Ol' Fatso, Get those reindeer off the roof.

You can find the lyrics of Donde Esta Santa Claus on the Web, but until now Ol' Fatso's have been missing. You'll agree that this is a public service that just had to be performed, so here they are. As you can see, this is the old familiar story of scepticism overcome by self-interest:

CHORUS:

Don’t care who you are Ol’ Fatso

Get those reindeer off the roof

Don’t care who you are Ol’ Fatso

Get those reindeer off the roof

No you can’t fool me because

There ain’t no Santa Claus

There ain’t no Santa Claus And I got proof.

There was a little fellow

Who just wouldn’t believe

There really was a Santa Claus

Even on Christmas Eve

And when one Christmas Eve he heard

A clatter overhead

He opened up his window wide

And this what he said:

[CHORUS]

Though Santa Claus had brought him

A big bag full of toys

Enough of Christmas presents

For a dozen little boys

Some choo choo trains and cowboys

And a whole Apache tribe

The boy looked up and said,

Oh no! I ain’t taking no bribes

[CHORUS]

Well next year Santa came around

And brought a favourite toy

To everybody but a certain

Unbelieving boy

The moral of this story

Is very sad but true

If you don’t believe in Santa Claus

He won’t believe in you

Don’t care who you are young fellow

Keep those reindeer on the roof

Don’t care who you are young fellow

Keep those reindeer on the roof

Oh you fool no-one because

There is a Santa Claus

There is a Santa Claus

And I got proof.

Yes, there is a Santa Claus

And I got proof.

Spanish-born child actor Augie Rios released a handful of singles, 1958-64. Country Paul, posting to Spectropop in 2004, outlines Augie's career on stage, TV and record, citing several sources on the Net.

07 November 2006

▶︎ That brownstone house where my baby lives...

At the risk of this becoming Oboe: The Blog, I must mention another oboe-enriched delight that leapt out at me from a Gene Pitney compilation at the weekend: that strange and unique 1963 hit Mecca.

At the risk of this becoming Oboe: The Blog, I must mention another oboe-enriched delight that leapt out at me from a Gene Pitney compilation at the weekend: that strange and unique 1963 hit Mecca. As with my first post on the oboe, I was a bit tentative about identifying the instrument in Mecca as an oboe. True, that does seem to be a flute in the instrumental break but Ted Swedenburg, over at hawgblawg, is with me in also hearing an oboe. It appears first in the the introduction, then throughout the song, embellishing a smashing rhythmic arrangement.

[Listen to excerpts: intro; instro break.]

Ted played Mecca on his radio show on KXUA last year, and I recommend the appreciation and commentary he posted about this weird song (Ted's word):

It opens with a vaguely Eastern sounding oboe, playing a riff that sounds like what passed for snake charmer music in all the cartoons I saw growing up in the ‘50s.

Ted confirms what I suspected, that little seems to be known about the writers, Neval Nader and John Gluck Jr. As my friend Phil commented, Mecca proves that all songwriters have at least one great song in them.

There is something unusual about Mecca. It's hard to say whether the colloquial use of 'Mecca' stood out at the time, or whether it only does that in our time, when such religious references are used less lightly.

The lyrics go beyond the secular use of 'Mecca' as a metaphor, though, by including its religious origins, and that is unusual in a romantic pop song. There's a Romeo and Juliet thing going on here, East side of the street versus West side of the street (get it?), and the guy 'worships at her shrine':

Each morning I face her window,

And pray that our love can be,

'Cause that brownstone house where my baby lives

Is Mecca, Mecca to me

Ted points out the faux-Eastern elements of the arrangement, which do conjure up a caricature of the Middle East. To my ears, it's only a side-step away from the slapstick desert scenario of Ray Stephens' Ahab the Arab (1962).

It's not surprising that Gene Pitney's repertoire could accommodate such a quirky masterpiece as Mecca. His repertoire was wonderful and wide, so wide that his list of hits in one place won't always match his list of hits in another.

In Australia, for example, Billy You're My Friend (1968) charted in Melbourne, Adelaide and Brisbane but not in Sydney; Hawaii (1964, the B-side of It Hurts To Be In Love) charted in its own right in Adelaide, Sydney and Brisbane but not in Melbourne. Neither of those songs was a Top 40 hit in the US or Britain (although Hawaii's A-side was).

Pitney told his Australian audiences that he started including Who Needs It (1964) in his Australian sets because he noticed Aussies calling out, 'Who needs it?' and realised they weren't heckling him but were asking him to sing his Australian hit, a B-side elsewhere, a song that he'd all but forgotten.

This is why a Gene Pitney Best Of... with 18 tracks is never going to please every fan in every town in the world.

Even Mecca, a #12 in the USA that was popular in Australia (#4 Adelaide #5 Brisbane #7 Sydney & Melbourne) didn't make the Top 40 in Britain.

The first of three times I saw Pitney in concert over the past fifteen years or so, it was in a licensed cabaret in our provincial Australian city. All night a drunk in the audience kept yelling out, 'Do Mecca, Gene!' and, 'Gene, when are ya gonna do Mecca?' but Gene (quite rightly) declined to notice him, and he never did do Mecca, not that night or on his two later visits to our town, when he performed in an old but newly refurbished concert theatre where he clearly felt more at home.

On the third occasion, Jamie came too, and you can read his tribute to Pitney over at his blog. Nothing I can add to that, really, except that we wish there could have been a fourth time.

___________________________________

Brownstone house image from www.BrownstonesDirect.com.

04 November 2006

▶︎ Iva Davies, oboist

Dave, who was flautist and saxophonist with Sydney band Flake, played with Iva Davies on a recording of film music written by Steve Gard. This was some time before Icehouse (initially Flowers) was formed, and it seems to have been Iva Davies' first recording.

Dave tells the story at his Burning Mountain Studio blog:

In 1972 Iva was a student at the Sydney Conservatorium of Music. (Steve and myself also went there at other times). Steve was involved with the New Theatre at the time, where he met Chris Noonan (these days a Hollywood director [Babe, etc]) and Chris asked Steve to score music for a movie called Garbo he was making. Steve wrote the theme music and we recorded it at ATA studios in Glebe. Iva played oboe and tuba, Steve played guitar and piano and I played flute.

01 November 2006

▶︎ Media on demand, 19th Century: the Electrophone

Picture this: Marcel Proust, in 1911, is in his cork-filled room in Paris, writing À la recherche du temps perdu.

And he's listening to a live opera broadcast through a set of headphones.

That would've sounded impossible, some kind of sci-fi time warp, until I heard the story of the Electrophone on BBC Radio 4's Archive Hour last week.

The Electrophone was a British subscription radio service that used a telephone connection. It was available from 1895, a couple of decades before wireless broadcasting, when Queen Victoria was still on the throne. Proust was a subscriber to the earlier French version, known as the théatrophone.

Electrophone programs were live feeds from theatres and music halls, featuring the stars of the day. They even transmitted services from a London church that concealed some of the electronics inside a hollowed-out Bible, for decorum's sake.

Subscribers would contact the Electrophone company in Soho by ringing up their regular telephone switchboard, then request a program from whatever was being transmitted at that time.

At the receiving end, several listeners could hook up using headsets kept hanging on a purpose-made wooden stand, a listening-post (as we still call such a set-up in classrooms). The photo, from the British Museum's Connected Earth website, shows a 1905 model.

In France, le théatrophone was launched in 1890. Marcel Proust was a fan, and would listen to live feeds of Wagner or Debussy while writing. Proust was enthusing about the service around 1911: the image of a writer, working to music from a headset, is mundanely familiar to us now, but it's startling to find it so long ago.

Carolyn Marvin, in When Old Technologies Were New, writes about experiments as early as 1880, when visitors to the Paris Exposition Internationale d'Electricite listened to opera and theatre transmissions through a théatrophone hook-up.

In England in 1889 a novel experiment permitted 'numbers of people' at Hastings to hear The Yeoman of the Guard nightly. Two years later theatrophones were installed at the elegant Savoy Hotel in London, on the Paris coin-in-the-slot principle. For the International Electrical Exhibition of 1892, musical performances were transmitted from London to the Crystal Palace, and long-distance to Liverpool and Manchester. In the hotels and public places of London, it was said, anyone might listenThe United States Early Radio History website has a marvellous photo from 1917 of an Electrophone being enjoyed by a group of convalescing soldiers in London, listening to 'the Latest Music Direct from the Theatres and Music Halls'.

to five minutes of theatre or music for the equivalent of five or ten cents. One of these places was the Earl's Court Exhibition, where for a few pence 'scraps of play, music-hall ditty, or opera could be heard fairly well by the curious. (Carolyn Marvin, When Old Technologies Were New: Thinking About Electric Communication in the Late Nineteenth Century, New York: Oxford University Press, 1988; paperback, 1990. Excerpts posted to Dead Media Working Notes)

The Electrophone service held out until 1925 when the wireless began to take hold, and the writing had been on the wall by 1923: see the news report at the United State Early Radio History website.

(Sadly, the Electrophone story from Archive Hour is no longer online: they don't seem to be into archiving past programs at the BBC as much as they are at our ABC.)

16 September 2006

▶︎ Oboes

Look, some of these might not be oboes at all. I could be swooning over an oboe when I'm really hearing a clarinet or a cor anglais or... I don't know what else: a penny whistle? I believe we're at least talking woodwinds, but an electronic keyboard could be leading me astray. Maybe I should go back to The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra.

Look, some of these might not be oboes at all. I could be swooning over an oboe when I'm really hearing a clarinet or a cor anglais or... I don't know what else: a penny whistle? I believe we're at least talking woodwinds, but an electronic keyboard could be leading me astray. Maybe I should go back to The Young Person's Guide to the Orchestra.

With that caveat, these are some songs that show how an oboe (or something that sounds like an oboe), tastefully arranged and sparingly introduced, can be the making of a pop record:

The Chiffons - Sweet Talkin' Guy (1965)

This shuffling piece of girl-group pop has a joyful groove that makes you smile, but lyrics that are about heartbreak and deception, one of those contradictory songs mentioned in an earlier post. Still, the tasteful oboe line in the instrumental break does have a plaintiveness about it. (Sweet Talkin' Guy's writer credits are to Eliot Greenberg and Robert Schwartz, co-founders of Laurie Records, with Barbara Baer and Douglas Morris.)

Harpers Bizarre - Cotton Candy Sandman (1968)

Written by Kenny Rankin (mentioned earlier in connection with Nick Lampe) who had released it himself in 1967 on Mind Dusters. The lyrics are sentimental, but if that's not your bag just focus on the light, sunshiny melody, arranged in a perfect mix of orchestral instruments (strings, oboe and harp) driven along by a tight pop rhythm section.

Honeybus - I Can't Let Maggie Go (1968)

British band Honeybus gave us at least two classic songs: (Do I) Figure In Your Life (1967) - famously recorded by Joe Cocker - and I Can't Let Maggie Go, both written by Honeybus's Pete Dello (Peter Blumson). He used two oboes, a cor anglais and a bassoon in the arrangement, inspired by a work by Mozart for woodwinds (Welch & Soar, One Hit Wonders, 2003).

Rod Stewart - Handbags And Gladrags (1970)

Rod at his peak, with oboe intro, on a Mike D'Abo song that later grew legs of its own, thanks in part to its airing as the theme for The Office. See my page on its history, over at the website.

Dream Academy - Life In A Northern Town (1985)

I can't resist this: a band whose onstage line-up includes an exceedingly cool oboe player who also sings back-up vocals. The oboist is Kate St John, whose discography includes sessions with Van Morrison, Kirsty McColl and Nigel Kennedy, as well as albums in her own right. More at KateStJohn.co.uk. Meantime, press Play:

Image of oboist courtesy of the Special Collections Department, University of Iowa Libraries.

12 September 2006

▶︎ Slow versions

Nothing prepared me, though, for Marvin Gaye's downright bouncy 1963 original of Wherever I Lay My Hat (That's My Home). I'd already become attached to Paul Young's slow, haunting version from his 1983 album No Parlez.

In the same way, I'd got to know the 1924 Isham Jones-Gus Kahn song It Had To Be You through a slow version. It was on 'S Awful Nice (1958), an album by Ray Conniff, whose wordless-chorus-plus-brass arrangements were a big part of the soundtrack of our household when I was a kid in the late 50s and early 60s.

I heard enough slow arrangements of It Had To Be You to make me admire it in the same way as I admired Ray Noble's The Very Thought Of You, another slow, sweet and romantic song from songwriting's golden age.

I didn't hear Isham Jones's own recording of It Had To Be You until recently, and it turns out to be an upbeat Roaring 20s dance number in the vein of Tea For Two. For me it doesn't have the same allure as it does as a slow song.

It might depend on how you first hear a song, and I might need to soften my harsh opinion of jazzing it down.

04 September 2006

▶︎ Dylan and the Sound

It is always the sound that interests Dylan about a song, and one of the reasons that he is only semi-articulate in interviews is that you can’t really describe a sound. It was [Woody] Guthrie’s sound that attracted him, not Guthrie’s lyrics.

29 August 2006

▶︎ I never missed Glenn A. Baker's Rock'n'Roll Trivia Show

The evening before, I'd seen Glenn A. Baker on Talking Heads (

the transcript on line, and it's as good a source as any for an outline of his life and career). It was nice to hear his enthusiast's voice again, that friendly treble that sounds as if it's about to break into laughter.

the transcript on line, and it's as good a source as any for an outline of his life and career). It was nice to hear his enthusiast's voice again, that friendly treble that sounds as if it's about to break into laughter.For a couple of years in the late 70s I never missed Glenn A. Baker's Rock'n'Roll Trivia Show. I picked it up from Sydney late on Sunday nights on 2JJ, the ABC's AM station that later went FM and became the national youth network Triple J. I even had a little lapel button that said I NEVER MISS GLENN A. BAKER'S ROCK'N'ROLL TRIVIA SHOW. (It's a historical artefact now, listed at the Powerhouse Museum, though I think mine was an earlier version.)

I found the Trivia Show when I was cruising the dial and heard The Martian Hop, a song I hadn't heard on radio for ages and hadn't really expected to hear at all. I thought, any friend of stuff like that is a friend of mine.

The Trivia Show turned out to be a rich source of lost and obscure pop. The emphasis was often in the Brill Building-girl group-Phil Spector area (Glenn would've been at home at Spectropop), and it could easily have been called the Pop Trivia Show. The celebration of well-crafted pop reminded me Awopbopaloobopalopbamboom (The Story of Pop), that exhilarating guidebook written by another enthusiast, Nik Cohn.

I liked the way Glenn highlighted the work of songwriters, who he believed provided the underlying structure of pop history. On Talking Heads, he spoke about looking at the finer detail on record labels, examining those words...within the brackets, something I'd always done too. One of my aims at the website is to give credit to songwriters, who are often - along with arrangers - the unsung heroes of popular music.

The stroke of genius behind the Trivia Show was the way it blended oldies with current music that fitted the same sensibility. This didn't mean anything as obvious as featuring revivalist bands like Showaddywaddy or Darts (although they would pop up sometimes, as did Glenn's own proteges Ol' 55). It did mean, though, that you could hear Glenn interview Del Shannon one week and Ric Ocasek of the Cars another week.

It meant that when Glenn mentioned the girl group sound he could just as easily play The Cake's sublime Baby That's Me (1967, an oldie I discovered through the Trivia Show) or Kirsty McColl's maddeningly infectious debut single They Don't Know (1979).

Dave Edmunds, who owed heaps to rockabilly and Chuck Berry and Spector, but recast it all for the times, was often on the Trivia Show. I have a feeling one of the first times I heard XTC was on the Trivia Show: could it have been Life Begins At The Hop?

If there was ever some song from the 60s that I longed to hear, I would write a letter, in an envelope with a stamp, to Glenn A. Baker: this was before instant downloads and vast catalogues of reissues ordered on the Net. He would usually play them, usually with enthusiastic approval. I remember him playing my requests for The Righteous Brothers' On This Side Of Goodbye, Leslie Gore's That's The Way Boys Are and Alan Price's I Put A Spell On You. [Listen to Glenn playing my requests at this follow-up post]

Well, oh well, early in 1980 we moved to another town where I could no longer pick up 2JJ on Sunday nights, and that was the end of that. But Glenn A. Baker's Rock'n'Roll Trivia Show, with its building of bridges between old style pop and late-70s New Wave and power pop had been part of my reawakening of interest in current popular music.

Which was nice.

▶︎ Where was I in the 70s?

Like what? Well, disco for a start, which seemed formulaic and mannered and I never really got it anyway; teenyboppers like The Bay City Rollers and David Cassidy who enraged me with their lame recyclings of great pop songs from my recent past; and try-hard pop artists with big heels and hair and gold chains on their chests who seemed to have lost the spark of the 60s and just couldn't reignite it. There were bits I liked: ELO and early Elton John, both of which I grudgingly related to as an extension of the 60s. Oh, maybe J.J. Cale, individual songs like Boys Are Back In Town or All The Young Dudes... my mind's a blank.

Looking back, I can see I was too much of a curmudgeon. I probably relied too much on Top 40 radio, and there would've been things to discover if I'd got out more. Somehow I let Led Zeppelin pass me by for contrary reasons, something to do with preferring the Yardbirds, or something: who knows what prejudice was driving me (until the late 90s when my kids started playing them and I realised what I'd missed out on). If I'd stepped sideways from disco I might've discovered some of the funk that I'm only hearing now through some of the classier mp3 blogs, and there was all that jazz if I'd known where to start.

What snapped me out of my torpour wasn't raw punk of the Sex Pistols' variety, but what came to be known as New Wave. That's a catch-all phrase, easily dismissed, but something was going on in the late 70s at the time I started noticing the likes of Elvis Costello and XTC: it sounded to me as if music had been asleep and had woken up with a start and taken up where it had left off in the late 60s.

I don't know if that stands up musicologically, but that's how it seemed in the musical history in my head, as I headed for my thirtieth birthday. I bought the soundtrack to a film called That Summer (1979). I knew nothing about the film, but the tape included such joyous rocky-pop as The Only Ones' Another Girl Another Planet and Eddie & The Hot Rods' Do Anything You Want To Do.

I wandered into a little record shop above a hardware store in Tenterfield, a country town in NSW, and found an audiocassette of XTC's Drums & Wires: I'd heard Making Plans For Nigel on the telly, and the album was startling in its innovativeness and musicality, and its nutty, off-kilter view of things.

I'd bought a tape of Elvis Costello's My Aim Is True by mail, through a record club (Watching The Detectives and Alison had been on the radio a lot) . When it went haywire on me I sent it back, and received an apology and a replacement, "another tape by the same artist": Elvis Presley's Viva Las Vegas. Some folks in record sales hadn't caught up with what was going on.

05 July 2006

▶︎ Presto = Alfredo = Moco

Posting about Boofhead reminded me of Presto, a daily comic that ran on the back page of the Melbourne Herald in the 50s and 60s.

Posting about Boofhead reminded me of Presto, a daily comic that ran on the back page of the Melbourne Herald in the 50s and 60s.Presto was a round-headed little man with a moustache who turned up from day to day in various roles: one day he could be a policeman, the next day a burglar or a ship-wrecked sailor. He often had his eye on a good-looking girl, but he had a formidable wife who was usually onto his case. The strip was all in pantomime, no dialogue.

I suspected it wasn't Australian, but it turns out to be from Denmark, where its title was Alfredo. WeirdSpace tells us, though, that it had appeared initially in the French newspaper Le Figaro in the late 40s, where it was entitled Presto, just as it was here. In the USA it was called Moco, derived from the names of Alfredo's creators, Jørgen Mogensen (1922-2004) and Cosper Cornelius (1911-2003).

Mogensen was a distinguished Danish cartoonist who created a number of comics. Defunct Danish site Rackham.dk had a cartoon at its Mogensen page that shows his characters meeting up with each other [archived version]. Alfredo/Presto/Moco is at the lower left, shaking hands with a later creation, Violin Virtuoso Alfredo.

________________

Image from Maurice Horn (ed.), The World Encyclopedia of Comics (1976)

03 July 2006

▶︎ Boofhead

You don't have to look far to find examples of boofhead in Australian English.

You don't have to look far to find examples of boofhead in Australian English.

It's time for Bozo and Boofhead to go, says a Melbourne Age headline about obnoxious footballers; an ABC radio site had Boofhead of the week, an inept home handyman. It appears in plenty of blogs, which may give you a flavour of its usage, and Google Image results for boofhead are also instructive.

I guess a boofhead is what Mark Twain would've called a puddenhead, maybe with some sense of what the Brits call a likely lad. A boofhead is a bit slow, maybe clumsy and unthinking, a likeable clot. It can be a friendly term (the inept handyman), but a boofhead can also be uncouth and boorish (the obnoxious footballers). You could say the behaviour of yer soccer hooligans is a bit boofy.

The image of Boofhead the character (above) is from R.B. Clark's daily comic strip. Boofhead ran in Sydney's Daily Mirror and in comic book reprints from 1941 until its creator's death in 1970.

It's one of those instantly recognisable Australian images, adopted by Mambo design and by the artist Martin Sharp for Regular Records. The Powerhouse Museum's website shows showed Boofhead on a 1966 Oz Magazine cover by Martin Sharp. There's even a statue of Boofhead in a park at Leura in the Blue Mountains.

You could say the strip itself has an endearing boofheadedness about it, with its daft situations and its two-dimensional artwork (as far as I know, Boofhead himself is always seen in profile, Egyptian-style).

John Ryan, the Australian comic strip historian, puts it this way:

Boofhead - drawn by Bob Clark and featuring a simplistically drawn, waistcoated young man with an elongated nose sheltered by a cantilever hairstyle - was amateurish and the humour mundane. It is difficult to fathom the reasons that this strip attracted readers but there can be no disputing its popularity. (In Panel by Panel: An illustrated history of Australian comics, 1979.)

An Australian National Dictionary updates page has citations for boofhead from 1941 and 1942, but doesn't mention the comic strip. I'm assuming the word predates the comic, and the comic helped popularise it, as John Ryan suggests: Boofhead brought back into common usage the term 'boofhead' in describing a simpleton or fool.

02 July 2006

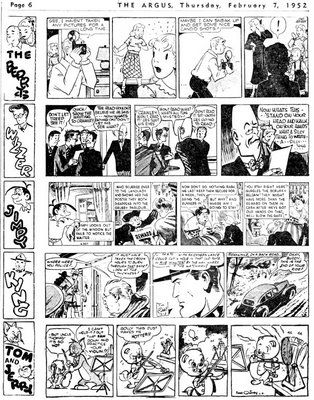

▶︎ Comics from The Argus

The Argus was a well-established morning paper that was closed in 1957 after it had been bought out by The Herald and Weekly Times, publishers of the rival Sun.

Our family took The Argus, and when it folded my main concern as a 6- or 7-year-old was the comics page. I remember being pleased to see that some of the Argus strips had migrated to our new paper, The Sun.

One of those was Carl Grubert's family sitcom strip The Berrys, which ended up running for years in The Sun. (At ComicStripFan.com there is a large page of Grubert's original artwork.)

Apart from the animated cartoon spin-off Tom and Jerry, some of the others on the Argus page are lesser known, at least to me:

Jimpy was a short-lived British fantasy strip for children that ran in the Daily Mirror from 1946 and folded in 1952. Maurice Horn (World Encyclopedia of Comics) believes it may have been a victim of opinion polls which consistently gave Jimpy a low rating but failed to ask children, its target audience. Jimpy's creator was Hugh McClelland.

King is King of the Royal Mounted, a US adventure strip created in the 30s by Western writer Zane Grey. At this time it was being drawn by Jim Gary. Bill Hillman has a fabulous page of King of the Royal Mounted covers from the 30s to the 50s at his Zane Grey Tribute Site.

Wizzer was an Australian comic strip about a public schoolboy inventor, Hermon Wizzer of Merryville College, surely one of the most obscure comic strips in the universe.

As far as I can see, Hermon Wizzer of Merryville College is mentioned only once on the searchable Internet (apart from some eBay listings which misspell it as Herman Wizzer), in spite of the numerous comprehensive comic strip sites to be found. It is only a mention, too, in a Michigan State University library catalogue, but it usefully points to John Ryan's Panel By Panel, which has a paragraph about it and reprints a daily strip from 1950.

Hermon Wizzer's home was The Argus, and it ran from 1949 till 1957, created by A. D. Renton and W. J. Evans, about whom, John Ryan says, little is known.

[Click on the image. It will open on a new page.]

01 July 2006

▶︎ Little Sport and Pop plus The Potts at the Coronation

Here's a comics section I scanned from the Melbourne (Australia) morning daily The Sun, June 3, 1953.

I believe Little Sport was usually a back sports page strip, but this was a special edition for the Coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, so Little Sport was bumped to the main comics section. There's a note on the back page directing readers to Little Sport inside the paper.

Allan Hogg, over at his excellent comic strips blog Stripper's Guide has a Sunday Little Sport in colour. It was an American strip, drawn by John Henry Rouson from 1948 till 1976. Rouson died in 2000 , aged 91. Like Presto, over at the evening Herald, it was an institution in the comics pages when I was a kid.

The other strips include Pop, a British strip, 1921-1960, created by John Millar Watt (J.M.) and taken over later by Gordon Hogg (Gog).

Jim Russell's The Potts, who on this day are in London for the Coronation, was a mainstay of the Australian comics pages for decades. It was created by Stan Cross, and first appeared in Smith's Weekly in 1919 as You and Me, later Mr & Mrs Potts. Jim Russell took it over in 1939 and it became a syndicated daily newspaper strip in 1950 as The Potts.

Suzy was another Australian strip, by Ian Clark. It ran in Murdoch newspapers from the late 40s until 1966.

Hopalong Cassidy was by Dan Spiegle, hired by Hopalong Cassidy actor William Boyd to create the strip in 1949. The strip ran until 1955.

One quaint feature of the comic strip in those days, along the top, was the little chapter heading, or teaser or... what was it called?

[Click on the image. It will open on a new page.]

References:

Maurice Horn (ed.), World Encyclopedia of Comics (1976)

John Ryan, Panel by Panel (1979)

26 June 2006

▶︎ The express train metaphor

One thing about Bernie Taupin's lyrics bugs me, though. The metaphor is a train, about how the singer was a mad tearaway in the past, an express train:

I used to be the main express

All steam and whistles heading west...

That makes sense, but then he sings about how he's changed:

But this train don't stop,

This train don't stop,

This train don't stop there anymore

Isn't that the thing about an express train, that it doesn't make stops? That's what makes it an express, right? So what's this about it not stopping any more?

Guess I've missed something.

09 June 2006

▶︎ The Sir Francis Drake theme

I was thinking about how you can fall for your own stereotypes.

Look at me, born in 1950, deep in Baby Boomer territory, just in time for a rock'n'roll childhood: Elvis's Heartbreak Hotel appeared in 1956, my Grade 1 year.

As if that weren't enough, The Beatles came along to span my teenage years so neatly, hitting our radios when I was 13 years old, and feeding me groovy new music until I was 19, when they broke up. They couldn't have planned it better!

So if I tried to sum up what I listened to in the 60s, I'd probably rattle off The Beatles, The Stones, all those other British Invasion bands like Manfred Mann and The Animals; solo artists like P.J. Proby and Dusty Springfield; The Beach Boys and The Turtles and Lovin' Spoonful of course; and Aussies like The Loved Ones, The Easybeats, Lynne Randell, Doug Parkinson... you get the picture.

If I ever want to evoke the 60s, give myself a pure, unrefined shot of what it felt like back then, I put on The Stones Aftermath (1966) and I'm immediately transported. Individual songs like Mike Furber's You Stole My Love or The Loved Ones' Everlovin' Man or even Cilla Black's Beatles giveway It's For You will do it for me as well.

But that's really my official line, the PR version, because the reality is more complicated.

As I was idly cruising the Lounge and Library mp3 sites recently, I downloaded a track that gave me such an unadulterated shot of my world at 14 or 15 that it made my head spin. This was a strong feeling of remembrance: you know, of things past, the effect that the madeleine cakes had on Proust's Marcel.

It wasn't some groovy song by The Mamas & The Papas or The Zombies that had  this effect. It was the theme music to Sir Francis Drake, a British TV series that starred Terence Morgan and Jean Kent.

this effect. It was the theme music to Sir Francis Drake, a British TV series that starred Terence Morgan and Jean Kent.

To begin with, this is a stirring composition in its own right, written by the British composer Ivor Slaney (1921-1988). The music evokes standing at the wheel of a creaking timber sailing ship, with the salty wind and spray in your face, surging through the icy waves to adventures in the name of Elizabeth I...

Okay, I have no idea what it's really like to do all that, but this music sets off all my well-conditioned responses to what films have told me it would be like, and it uses familiar conventions of Western film music: heroic trumpet fanfares, a majestic sailing ship tempo, swirling ocean wave strings, that sort of thing.

I was also startled to find how strongly it evoked watching afternoon TV in the living room of our house in Swan Hill. This was probably around 1965, when Sir Francis Drake was broadcast during the school holidays on the ABC (Australia).

Sir Francis Drake was absorbing viewing, one of those British series with classy actors and engaging scripts that convinced you this was real life at court and on the ocean wave in the 16th century. More than that, I was home from boarding school, so holidays were an intense time anyway.

Our soundtrack, the music we listened to and carried around in our heads, wasn't all 96 Tears and Psychotic Reaction. Now that I think of it, two of my most played LPs were the Charade soundtrack of Henry Mancini and Nelson Riddle's Route 66 and Other TV Themes, both of which seemed at the time to have a certain air of hipness, even though they were near the Middle of the Road.

While we wouldn't have come out as Matt Monro or Engelbert Humperdinck fans, we might have caught ourselves humming such MOR hits as Born Free or Les Bicyclettes de Belsize.

There were always songs like that on the charts, happily nestled in beside the groovier hits. Maybe it was our parents who put them onto the charts, or those kids who never dug the groovy stuff anyway, but they still formed part of that soundtrack in our heads, still took up space in our musical history.

Now, you can spend hours browsing and downloading whole albums of music from mp3 blogs dedicated to soundtracks, Lounge, Space Age, Exotica and Library Music, much of it digitalised from long lost LPs found in thrift stores. It's as if some of the music we dismissed outright and

classified under 'Parent' may have been worth a closer listen after all, and we may recognise more of it than we realise.

07 June 2006

▶︎ Outside, I'm masquerading, Inside, my hopes are fading

Speaking of lyrics, I was catching up on Series 2 of Scrubs on DVD when that joyous Cat Stevens song Here Comes My Baby popped up. The Tremeloes had the hit version, in 1967 (#4 UK, #13 USA), but Cat himself had released it on Matthew And Son (1967), and I believe that was the version heard on Scrubs.

Speaking of lyrics, I was catching up on Series 2 of Scrubs on DVD when that joyous Cat Stevens song Here Comes My Baby popped up. The Tremeloes had the hit version, in 1967 (#4 UK, #13 USA), but Cat himself had released it on Matthew And Son (1967), and I believe that was the version heard on Scrubs.Joyous indeed, and I break into a big chuckly smile every time I hear it: The Tremeloes record runs with that feeling, adding a party atmosphere with whoops and yelps of encouragement from the lads, and an interlude of merry whistling.

If you listen to the lyrics, though, you first hear this: In the midnight

moonlight I'll be walking a long and lonely mile. What's this about a long and lonely mile? Doesn't sound too joyous, does it? In fact here comes the guy's baby, and she's with another guy:

moonlight I'll be walking a long and lonely mile. What's this about a long and lonely mile? Doesn't sound too joyous, does it? In fact here comes the guy's baby, and she's with another guy:Here comes my baby, here she comes now,

And it comes as no surprise to me, with another guy.

Here comes my baby, here she comes now,

Walking with a love, with a love that's all so fine,

Never could be mine, no matter how I try.

So this is a song about unrequited love, or a break-up. Whatever the back story, the words seem to be at odds with the feel of the song.

Of course, it depends on how you look at it. The guy might be like Smokey Robinson's life of the party in The Tracks Of My Tears (recorded by Smokey's group The Miracles):

Although I may be laughing, loud and hearty,

Deep inside I'm blue.

Smokey tells it from the inside, behind the masquerade, so his song does sound sad, but maybe in Here Comes My Baby we're hearing it from the outside, as he laughs through his tears at The Tremeloes' record hop.

The same story, watching your baby with another guy, is told in a fine, overlooked song from the 60s, See The Way by The Black Diamonds.

The singer in See The Way isn't masquerading, he's not cracking hardy, he's good and mad. You can picture him with his mates, indignantly pointing out his ex with her new guy, so incredulous he can hardly get the words out: See the way, see the way, see the way she's walking with him...

With each new outrage he cries out at the start of the chorus, NOW LOOK! as if he can't believe his eyes, and by the last chorus he can hardly contain himself: YES!!! NOW LOOK!!! All of this anguish is propelled by dramatic guitar and drum lines: the whole thing is like a scene from a teenage opera.

See The Way is miles away from Cat's scorned but peppy lover, musically and geographically. The Black Diamonds were a 60s garage band from Lithgow, a coal mining town in New South Wales. Later (I'm reading from Ian McFarlane's Encyclopedia of Australian Rock & Pop) , they moved to Sydney and changed their name to Tymepiece, but along the way they recorded a local hit version of The Lion Sleeps Tonight under the name of Love Machine.

02 June 2006

▶︎ A few words from our lyricist

I keep getting emails from people looking for lyrics, usually to some obscure local hit that's impossible to find at any lyrics site. The other day, someone was after Frankie Davidson's Ball Bearing Bird.

I keep getting emails from people looking for lyrics, usually to some obscure local hit that's impossible to find at any lyrics site. The other day, someone was after Frankie Davidson's Ball Bearing Bird.

Really, I'm the last person to ask about lyrics. I'm a poor listener: I notice the beat, and the arrangement, and the vocals... but it's only the odd line or phrase that sticks in my mind.

It's not that I don't care about lyrics, but with many rock or pop songs I'm happy if the words just sound right: in fact I hate it when they don't sound right, whatever their meaning is.

If the vowels and consonants sound good with each other it doesn't matter so much if I don't take in the meaning, in the same way that Italian opera or Brazilian pop are incomprehensible but still enjoyable. Scat singers knew about that, and John Lennon's Ah! böwakawa poussé, poussé always sounded fine to me: I mean, let's face it, goo goo g’joob!

I'm not, like, against lyrics, nothing extreme like that: I always dug Simon & Garfunkel's words, and you can't listen to Nick Drake or Joni Mitchell or Tom Waits without taking in the lyrics. It's just that it's mainly fragments I notice or remember, the odd line or phrase. Fragments like these:

"Kathy, I'm lost," I said,

Though I knew she was sleeping

Simon & Garfunkel - America (Paul Simon - Art Garfunkel)

On Bookends, 1968

So you think you’re having good times

With the boy that you just met

Kicking sand from beach to beach

Your clothes all soaking wet

Traffic - Paper Sun (Jim Capaldi - Steve Winwood) 1967

The lyrics are by Jim Capaldi. See the 2002 Usenet discussion about the second verse's pitching lips, heard (plausibly) by some as hitching lifts. (The 'Lindsay Martin' in the discussion is me.)

"C'est la vie," say the old folks,

It goes to show you never can tell.

Chuck Berry - You Never Can Tell (Chuck Berry) 1964

Neat use of assonance. Check out those vowel sounds: C'est-say; old-folks-goes-show; never-tell.

The whole song is a slice-of-life masterpiece, a short story writer's catalogue of everyday details.

You study 'em hard and hopin' to pass...

Chuck Berry - School Days (Chuck Berry) 1957

And so it's my assumption, I'm really up the junction.

Squeeze - Up The Junction (Chris Difford - Glenn Tilbrook)

On Cool For Cats, 1979.

The lyrics are by Difford, I believe. This is the final line of the song. See the annotated lyrics from SqueezeFan.com (now off-line: archived). First, there's the nice near-rhyme of assumption and junction. Second, it uses a word that is unexpected in a pop song: assumption. Third, I love a song that leaves the words of the title right till the very end, rather than chanting it desperately all through the chorus.

I don't like you, but I love you.

The Miracles - You've Really Got A Hold On Me (Smokey Robinson) 1962

Genuine use by William 'Smokey' Robinson of the oxymoron as a literary device (not just any old contradiction, which most people these days seem to believe is an oxymoron). Also recorded famously by The Beatles on With The Beatles, 1963

Daniel is travelling tonight on a plane

I can see the red tail lights heading for Spain

Elton John - Daniel (Elton John - Bernie Taupin)

On Don't Shoot Me I'm The Piano Player, 1973.

Words by Bernie Taupin. Puts a picture in my mind that sums up the song.

Anyway, the thing is, what I really mean,

Yours are the sweetest eyes I've ever seen.

Elton John - Your Song (Elton John - Bernie Taupin)

On Elton John, 1970

Bernie Taupin again. British diffidence, summed up in colloquial language, and all the more romantic for it.

You stay home, she goes out...

The Beatles - For No One (John Lennon - Paul McCartney)

On Revolver, 1966

Routine language for a romance gone routine. For me the most perfect Beatles song, written by Paul, it's more like European cinema than a pop song. I was going to cut and paste the whole song, but see SongMeanings instead.

Here comes the twist:

I don't exist.

The Bonzo Dog Band - I'm The The Urban Space Man (Neil Innes) 1969

Produced by Apollo C. Vermouth, aka Paul McCartney.

Joneses, Joneses, all I see, page 19 to 23

Big big world can be unkind, the phone just took my last dime

Johnny Burnette - Big Big World (Fred Burch - Gerald Nelson - Red West) 1961

I know it ain't poetry, but it was on the radio a lot back then, and it tells a story, and it stuck with me.

South Silicon Way ...

It's an address, right? Maybe in a suburb of some English industrial city?

Sooorry... It's a misheard lyric, one I was so convinced of at the time that I couldn't believe it was actually So Sally can wait. That's the line in Don't Look Back In Anger by Oasis, 1995, on (What's The Story) Morning Glory.

Update: I later found a real South Silicon Way.

21 May 2006

▶︎ Mad Dogs and Originals

Listening again to Joe Cocker's live album of the Mad Dogs & Englishmen tour, I was startled to realise that this is now a generation old, a bit over 35 years.

At the time it was a joy, and I still marvel at how far rock'n'roll had come since my early teens, when the Beatles and the rest of the British Invasion took off. Joe Cocker wouldn't have been a star in 1963, he would've been laughed off the stage, and yet here he was in 1970, unkempt, idiosyncratic, unlikely and just wonderful.

I was thinking, as I do, about the sources of the songs, songs that were often reworked and transformed into something fresh. Apart from Cocker's (then) alarming delivery, credit is due to the arrangers, notably Chris Stainton - a member of Cocker's Grease Band - and Leon Russell, who produced Cocker in the studio and was the musical director of Mad Dogs & Englishmen.

Here's a list, with writers and original versions. I'm guessing that the Ray Charles versions of some of these songs would've been the significant ones for Joe Cocker.

Honky Tonk Women (Mick Jagger - Keith Richard)

The Rolling Stones, 1969.

Sticks and Stones (Titus Turner - Henry Glover)

Ray Charles, 1960.

Ray Charles had the original release: an earlier recording by co-writer Titus Turner was unreleased at the time. It was also recorded in the 60s by Billy Fury, Manfred Mann, The Zombies, The Righteous Brothers, and Mitch Ryder & The Detroit Wheels and others.

Cry Me A River (Arthur Hamilton)

Julie London, 1955.

Slow burning torch song rocked up by Leon Russell.

Bird On The Wire (Leonard Cohen)

Judy Collins, 1968.

Recorded by Leonard Cohen himself (in 1969), among others.

Feelin' Alright (Dave Mason)

Traffic, 1968.

Writer Dave Mason was a member of Traffic, along with Steve Winwood and Jim Capaldi.

Superstar (Leon Russell - Bonnie Bramlet + Delaney Bramlett)

Delaney & Bonnie, 1969.

Nothing to do with the rock opera, but a song originally issued as Groupie. More details at my own Superstar page at PopArchives.com.au.

Let's Go Get Stoned (Valerie Simpson - Nickolas Ashford - Josephine Armstead)

The Coasters, 1965.

Once again, Ray Charles had a version (1966), among others.

I'll Drown In My Own Tears (Henry Glover)

Sonny Thompson & Lula Reed, 1951.

Original title: I'll Drown In My Tears. Notably recorded by Ray Charles (1960) among others.

When Something Is Wrong With My Baby (Isaac Hayes - David Porter)

Sam & Dave, 1966, but hang on a minute:

The Originals gives the original to Charlie Rich, by a couple of months.

I've Been Loving You Too Long (Otis Redding - Jerry Butler)

Otis Redding, 1965.

Full original title: I've Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now).

Girl From The North Country (Bob Dylan)

Bob Dylan (with Johnny Cash), 1969.

On Nashville Skyline.

Please Give Peace A Chance (Leon Russell - Bonnie Bramlett)

A Mad Dogs & Englishmen original? I think so.

She Came In Through The Bathroom Window (John Lennon - Paul McCartney)

The Beatles, 1969.

On Abbey Road. Cocker had previously recorded this on the 1969 Leon Russell-produced album Joe Cocker!

Space Captain (Matthew Moore)

This is the original, here on Mad Dogs & Englishmen: Matthew Moore was one of the band. Matthew Moore's own version didn't appear until 1979, on his album The Sport Of Guessing. (The travel guide company Lonely Planet was named after co-founder Tony Wheeler's mishearing of lovely planet in Space Captain.)

The Letter (Wayne Carson Thompson)

The Box Tops, 1967.

Written by Nashville-based singer-songwriter Wayne Carson Thompson, aka Wayne Carson, whose demo version that 'sounded like the Everly Bros' was The Box Tops' source. Wayne Carson released his own version on Life Lines (1972).

Delta Lady (Leon Russell)

Joe Cocker, 1969..

Studio version on the album Joe Cocker! that predates Mad Dogs & Englishmen

16 May 2006

▶︎ More Kookies

There you can listen to two Jo Ann Campbell versions, one with a Tarzan call, one without; and what may well be the original version, by The Tree Swingers, along with the B-side.

Kees van der Hoeven (of John D. Loudermilk fame) was onto the alternative Jo Ann Campbell versions, at The Originals Problem-solving Forum: Original version had an Ape-call introduction. After release it was quickly withdrawn and re-issued with a decent no-ape version that became the OZ hit. (Post now deleted.)

Joop Jansen, also at the Forum, mentioned three other versions, all in languages other than English, now also listed by Phil.

06 May 2006

▶︎ Twenty Years on Wheels by Andy Kirk

Of course, I opened the book near the end, to see what he had to say about Killer Diller, the film I wrote about in an earlier post:

In 1948 the band was in a movie called Killer Diller. It was a comedy, and made at Pathé studios on East 116th Street. Convenient for me, because Mary and I had moved into 555 Edgecombe several years before - 1939 - so New York had been home-base since then. I didn't see the movie. I wasn't excited about it. I never got excited about big names and all that.Amy Lee comments:

But Andy did finally see that movie. In a phone conversation I had with him on 30 March 1980 he said he and Mary and Bernice had seen it "a couple of months ago" at the Thalia on Broadway and 95th Street, and that Butterfly McQueen was in it. They had paid regular admission to get in, but word got around that he was there, and at the end of the movie he and Miss McQueen - who apparently was there also - were called up on stage for a question-and-answer-session. "We also got our admission fee refunded," he said.

25 April 2006

▶︎ Jazzing it down

To some people this sounds sophisticated, but that's only because they don't let kids into nightclubs. To me it sounds like missing the point of a classic song. Fred Astaire didn't sing it that way, and he was plenty sophisticated for a gawky looking guy.

Because a song like The Way You Look Tonight (Dorothy Fields - Jerome Kern) is romantic and has a sweet melody, it's a sitting duck for interpreters who think that means slow and dreamy.

If you listen to a lot of music from the 1930s (at the peak of what Alec Wilder called the age of The Great Innovators), you find that even the most tender of love songs could still have loads of rhythm: you could dance to them, and they kept their tenderness.

This was also the Swing Era, after all, and there was a lot of, like, swinging going on back then. (The Way You Look Tonight was first heard in a film called Swing Time.) It might've been the olden days, but they didn't spend all their time in the parlour, singing light opera ballads around the pianola.

It's worth remembering the context of the song as Fred Astaire first sang it, in Swing Time (1936).

It's worth remembering the context of the song as Fred Astaire first sang it, in Swing Time (1936).

He and Ginger Rogers have had a tiff, and she's retired to the bathroom, shutting him out. Fred sings this meltingly lovely tribute to her, through the closed door, and she melts. In fact, she reappears, halfway through shampooing her hair.

The pace is brisk, Fred's delivery is assertive. Jerome Kern's melody conveys regret but Fred sounds positive, ready to move on but thankful just to have known her. In the studio recording the pace is enhanced by a foot-tapping rhythm section. [YouTube]

For me, this tension between regret and a more upbeat counting of your blessings is the point of the song: take out the rhythm and the song loses its backbone. And let's face it: some mournful, lovesick guy who sounds as if he's about to swoon all over the apartment floor was never gonna seduce Ginger.

In the 50s and 60s, when a rock artist took an old ballad and reworked it with a beat, it was called jazzing it up. Rockin' Rollin' Clementine was Col Joye's jazzed up version of Clementine. This sort of thing was sent up by Peter Sellers as a cockney pop star named 'Iron' (cf. Tommy Steele) who is interviewed by the BBC about his rockin' version of the Trumpet Voluntary.

And jazzing it down? That's what I call it when a fine, rhythmic song like The Way You Look Tonight is slowed down and given a lethargic jazz interpretation.

There was already a lot of this about when I was a kid in the 50s: ballad crooners, vocal groups, lush string orchestras and smoky nightclub singers, all trying hard not to sound like anything from the 30s.

My impression is that it started in the early 40s. The reasons are varied: swing bands lost personnel to the armed forces, wartime cutbacks affected touring, and the ASCAP boycott (1941) and the Musicians' Ban (1942-44) disrupted radio performances. Vocalists became the big stars and smaller comboes on independent labels got a break.

By the late 40s and early 50s, sweet, swinging records from the 30s probably sounded old-fashioned anyway, a harking back to the pre-war years and the outbreak of war. Certainly, radio in the late-40s and early 50s was full of mediocre novelty songs and cowboy music. That's what happens in pop music: things pass their use-by date.

Nowadays, though, when sophisticated jazz is mentioned, you can be sure there's a spot of jazzing it down in the offing, and it doesn't always make me melt.