• someone regarded as old by the speaker...

• something old, especially a popular song

1. Real music: are we there yet?

You can listen to a lot of oldies at YouTube now, and they attract a lot of comments from oldies.

Some YouTube commenters of my generation can't celebrate the music of their youth without adding that, by contrast, artists these days can't sing, can't play, and don't know how to write songs. (Oh, and they are not as well groomed. Probably not a musical issue.)

Of course it's not true: the sounds are different, but every generation has its geniuses and their mediocre imitators. It's doubtful whether the commenters have actually listened to much current music, which I admit is now dizzyingly fragmented and does take some effort to get a handle on. The days are long gone when "current music" pretty much meant the few songs that were being played on the radio this week.

In any case, it sounds too much like reactions from our parents' generation to rock'n'roll (to take one inter-generational scenario).

Examples are easy to find. From 1964, a feature writer sums up the Beatles: This badly-in-need-of-a-haircut group can't sing.....period [link; my hyphens]. And from 1965: a music publisher complains that lyrics this day and age are appalling and are rendered by so called singers with so called voices.... [link], and a columnist hopes for a revival of big band music for those of us who still enjoy dancing to real music... [link].

At YouTube today you will see the phrase real music used to boost the music of the past. A comment addressed to youngsters advises them that a Billy Preston track from 1974 is real music.

|

| Daily Telegraph (UK) 1904 [link] |

Journal because it will feature not ragtime nor "popular" music but real music [link]. (My impression is that real music c.1910 could also mean live as opposed to recorded music, still relatively new-fangled but gaining popularity.)

---

2. When too much is barely enough.

You'll see comments under an old song at YouTube where the user "misses" the music of their youth. They pine for the 60s when the music was great. They want to go to back to the 70s just so they can hear all these great songs.

It would too clever of me to point out that they have just listened to one of those great songs, right there at YouTube. They can repeat the track or save it for later, or browse thousands of others. How could they be missing it?

Through streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music, as well as YouTube, we can now access mountains of recorded music from any time in the history of the recording industry. Blimey, here's Billy Murray from 1911, off an Edison cylinder: Spotify

It's true that Spotify and Apple Music don't stream unreleased material or tracks that have never been reissued.

Luckily though, YouTube has gone beyond its remit of being a video site to become a repository of music so vast that you seem to be able to find almost any track you can think of.

This has happened partly because many serious record collectors have posted their collections to YouTube, often with just a still photo of the 45 on the video screen.

If you want to avoid the ads, and the amateurish slideshows and animations that accompany many songs, you can upgrade and listen on the Spotify-styled YouTube Music app.

|

| British Invasion cloud at Every Noise |

If you're short of genres, you could take a peek at the clouds of over 6,000 of them at Every Noise At Once, each with a link to a Spotify playlist. Japanese chill rap? No problem, and here's the playlist, with links to 15 related playlists including Guatemalan pop and Malaysian Hip Hop.

At this point, I'm starting to sympathise with the YouTube commenters. Part of me does miss switching on a Top 40 radio station deep in the 60s and listening to whatever they played, song after song, without any choices apart from twiddling the dial across to a rival station.

---

3. You mean there never was a golden era?

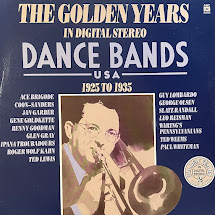

Years ago I wrote to Graham Evans at the ABC's Saturday night radio show Sentimental Journey. I posted a letter, in an envelope with a stamp: it was 1983. I was looking for the name of a 1930s song I'd heard. (It was Bunny Berigan - I Can't Get Started, which shows how little I knew at that stage.)

I also commented on the surprisingly high quality of music that he was playing from the 30s. When Evans wrote back with the name of the song, he surprised me by adding that there was plenty of bad music in the pre-WW2 era, and he was selecting the cream of it for his program. So my impression of a golden age was flawed, and I admired his candour.

When it comes to the music of our youth, we curate our listening so that we select our idea of the best of the era. We forget the sentimental balladry and corny novelties that sat side-by-side with the some of the grooviest songs in history.

There were second rate and third rate artists in our youth just as there are now. Try listening to an album by some of our idols from the 60s that had one or two hits filled out with mediocre copycat compositions, or pedestrian covers of other people's hits.

I'm sure that in Bach's or Mozart's time there were hacks churning out paint-by-numbers compositions, but we tend to stick with Bach and Mozart and their gifted contemporaries.

---

4. You had to be there.

I sympathise on one other point with my contemporaries who wish they could travel back in time, even though I go along with the killjoys who reply with lists of diseases and injustices you would endure if you did manage to slip back to 1965.

Replaying the music of your youth lacks the experience of hearing the music unfold as it appeared, in the context of the times.

The Beatles delivered surprise after surprise during my teenaged years, from the first trickle of singles on Australian radio in 1963, through a series of albums that (for me) culminated in the scintillating Abbey Road in 1969. The 3,000 mainly teenaged fans who swarmed Carnegie Hall in 1938 to hear Benny Goodman's orchestra were having that same experience, and although I have listened to a lot of Goodman's records from that time, I can never replicate the joy of being there, at that time, as the narrative unfolded.Link:

• Every Noise At Once: over 6,000 musical genres mapped with playlists and artist clouds

Benny Goodman And His Orchestra (Gene Krupa, drums) - Sing, Sing, Sing (Carnegie Hall Concert, 1938)